It’s intriguing that, on the day the Article 50 letter is delivered, the loudest voices around the kind of Brexit we’ll get are still those of the hardliners. Perhaps this is not surprising, given PM May’s strategy of aligning herself with them prior to the start of negotiations, and the position of the rabid right-wing press.

But at the end of the day, Brexit is an internal battle for the Tories, coupled with a political strategy for neutering the UKIP threat, at least in Tory-oriented territory. What seems to have been forgotten is the strong pro-EU balance among, not just MPs in general, but Tory MPs specifically.

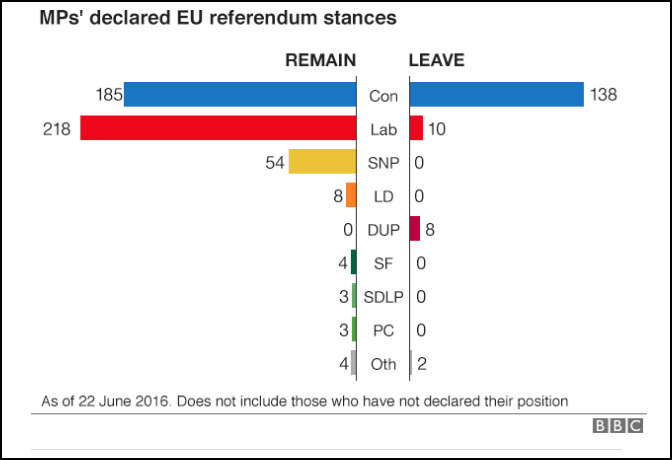

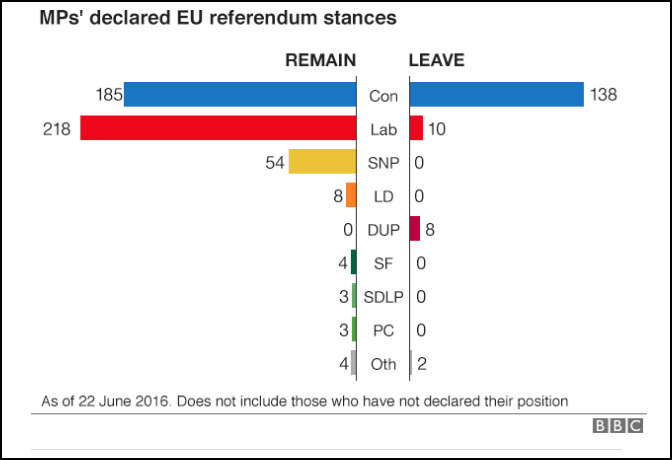

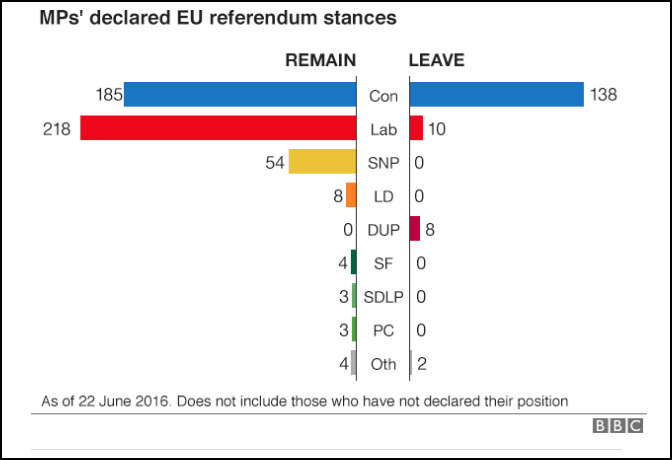

Here’s a breakdown of the UK MPs position re Brexit in 2016, PRIOR to the Brexit vote on June 23rd:

Amongst these 185 remain Tories is Theresa May herself. So why would she be pushing for a hard brexit, as so many red tops and Kippers seem to think? The answer, of course, lies in the positions to be taken at the start of negotiations. These, in the UK government’s case, have little to do with the destination of these negotiations, but everything to do with giving EU negotiators much of what they want. A hint of this strategy was revealed in a Spectator editorial from December 2016. To quote:

Britain… has decided to press ahead with plans to join an EU-wide patent system. This is a major overhaul, requiring UK courts to give up jurisdiction over patents, pooling sovereignty with the rest of Europe….We might be witnessing the first example of Mrs May’s Brexit strategy — to leave the EU, but opt into the agreements that we find agreeable. The price for this would be to accept the supremacy of the European Court of Justice, something that had been considered off the agenda. But on patents, at least, Mrs May’s government has planned to accept the ECJ’s writ.

In other words, sector by sector, the UK government will aim to negotiate agreements that essentially mean paying the EU for access to these sectors, and under EU jurisdication. This will prove expensive, and will require giving up “sovereignty” to the extent that, following the Great Reform Bill, the UK parliament will be required to enact UK legislation in these areas that mirrors EU law.

All of this will probably be sellable to the Brexit mob with a little smoke and mirrors about all laws being passed at Westminster. But what of the EU? What cannot be seen to come to pass is the cherry picking that threatens membership’s raison d’etre. Even Norway is required to accept the free movement of peoples in order to gain paid access to the single market. How will the UK government get round this sticking point?

The obvious route is to pick up on ex-PM Cameron’s negotiated deal prior to the referendum, but simply try to nail the same deal from the outside rather than from the inside of the EU. That deal, which limited EU migrants’ rights to a range of welfare benefits for the first 4 years, could well re-appear in another form as part of the final Brexit agreement, seen on one side as limiting immigration, and on the other as confirming the right to the free movement of peoples. But the key to a final agreement lies in PM May’s real wishes, Looking at the political numbers, and despite the rhetoric, they do not seem to be hard Brexit.

All this has obvious repercussions for the situation in Scotland. Not for nothing is May arguing that a second referendum should be called only once the final details of the Brexit deal are known. My strong suspicion is that May is going to aim for a soft Brexit that would outflank the SNP’s position of offering voters in Scotland a choice between full membership and no EU access. A soft Brexit, a sort of neo-Norway model, is attractive to Scottish voters, including many YESers who voted to leave the EU. My advice to Nicola Sturgeon would be to keep your powder dry, and accept that we should wait until the details of the deal are known before actually calling IndyRef2.

It might well be that the EU cannot accept, yet again, a privileged position for an outside UK, after years of insider privileges. But if a deal is struck, to be magnanimous in accepting a soft Brexit would essentially confirm the Scottish government’s position set out in the Scotland’s Place in Europe paper. The reasoning behind IndyRef2 is gone. The Scottish government needs to remain open to both outcomes, and make more of the distinction between having the power to call a referendum, and actually calling it.

This is a rare surname of Gaelic – Scottish origins. It derives from the word “griasaich” and can have several meanings including embroiderer, decorator and more latterly, shoe or hose maker. The surname is unusual in that it is occupational when most Gaelic names were patronymics, and based upon nicknames for the original chief of the clan. It is said that Grassick is most popular in the far north and specifically Aberdeenshire, where the pronunciation is as Gracey! As a result that there are spellings as Grassie and Grass, and indeed these seem to predate the actual Grassick recordings with that of John Grasse of Kirktoun of Crathe appearing in the tenants list in 1539. However it is more likely that earlier registers have gone missing, since the keeping of such items in the past was not given any great consideration. Other early examples of recordings include Donald Graycht at Lochalsh in 1548, Elspet Grassiche of Tullochaspak in 1612, and David Grassiche of Kepache. He was a bit of a lad who was accused of “violence” in 1617, although his fate is not known. Another to fall foul of the authorities was Alexander Gresiech of Towie in 1669. He was accused of curing cattle by charming them!

This is a rare surname of Gaelic – Scottish origins. It derives from the word “griasaich” and can have several meanings including embroiderer, decorator and more latterly, shoe or hose maker. The surname is unusual in that it is occupational when most Gaelic names were patronymics, and based upon nicknames for the original chief of the clan. It is said that Grassick is most popular in the far north and specifically Aberdeenshire, where the pronunciation is as Gracey! As a result that there are spellings as Grassie and Grass, and indeed these seem to predate the actual Grassick recordings with that of John Grasse of Kirktoun of Crathe appearing in the tenants list in 1539. However it is more likely that earlier registers have gone missing, since the keeping of such items in the past was not given any great consideration. Other early examples of recordings include Donald Graycht at Lochalsh in 1548, Elspet Grassiche of Tullochaspak in 1612, and David Grassiche of Kepache. He was a bit of a lad who was accused of “violence” in 1617, although his fate is not known. Another to fall foul of the authorities was Alexander Gresiech of Towie in 1669. He was accused of curing cattle by charming them!